How do I Verify my Vote

Published:

This is a summary of our paper “Comparing ‘Challenge-Based’ and ‘Code-Based’ Internet Voting Verification Implementations“ authored by myself, Jan Henzel, Melanie Volkamer and Karen Renaud, to be published at the INTERACT 2019 conference.

Ensuring the integrity of voting devices is a well-known and widely discussed problem for Internet voting. Web security vulnerabilities and malware on personal devices make it hard to prevent vote manipulations at the voting client.

The need for verification

Imagine an attacker gains control over the voting client on your personal device. Such an attacker would be able to change any vote you cast replacing it with another vote of their own choosing. The scenario is not that unrealistic, as shown, for example, by an attack against the New South Wales voting system [1]. During the 2015 election, a group of security researchers managed to insert their code into the voting client of the election’s Internet voting system. The code potentially allowed an attacker to change votes as they are cast during the election. By the time the vulnerability was removed, around 19,000 votes had already been cast. It remains an open question, whether any of these votes were manipulated by an unknown other exploiting the vulnerability.

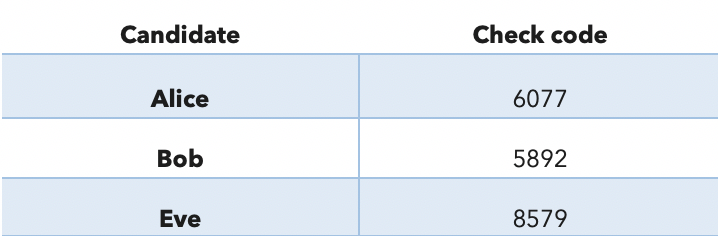

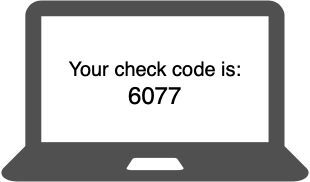

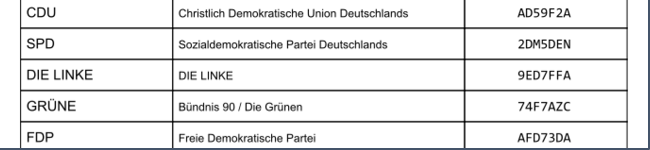

One way to combat such issues is to implement cast-as-intended verifiability. The idea is that the voter uses an external source to verify that their vote has not been modified by a malicious voting client. An example of such verification is the use of secret codes printed on paper sheets and distributed to voters before the election — the so-called code-based approach [2]. These codes are compared to the output provided by the voting website to ensure that the correct vote has been submitted to the voting system.

|  |

|---|---|

| Paper code sheet | Voting website |

A code-based verification with the voter casting a vote for Alice.

Simply providing voters with the technical means to verify their votes is insufficient. After all, Internet voting systems are not only used by computer scientists and IT experts. If verifying is too complicated people will not be able to verify their votes. So, an attacker who wants to manipulate an election’s outcome would succeed by manipulating the votes of the general population. Designing usable verification is critical to the security of the elections.

Testing verification usability

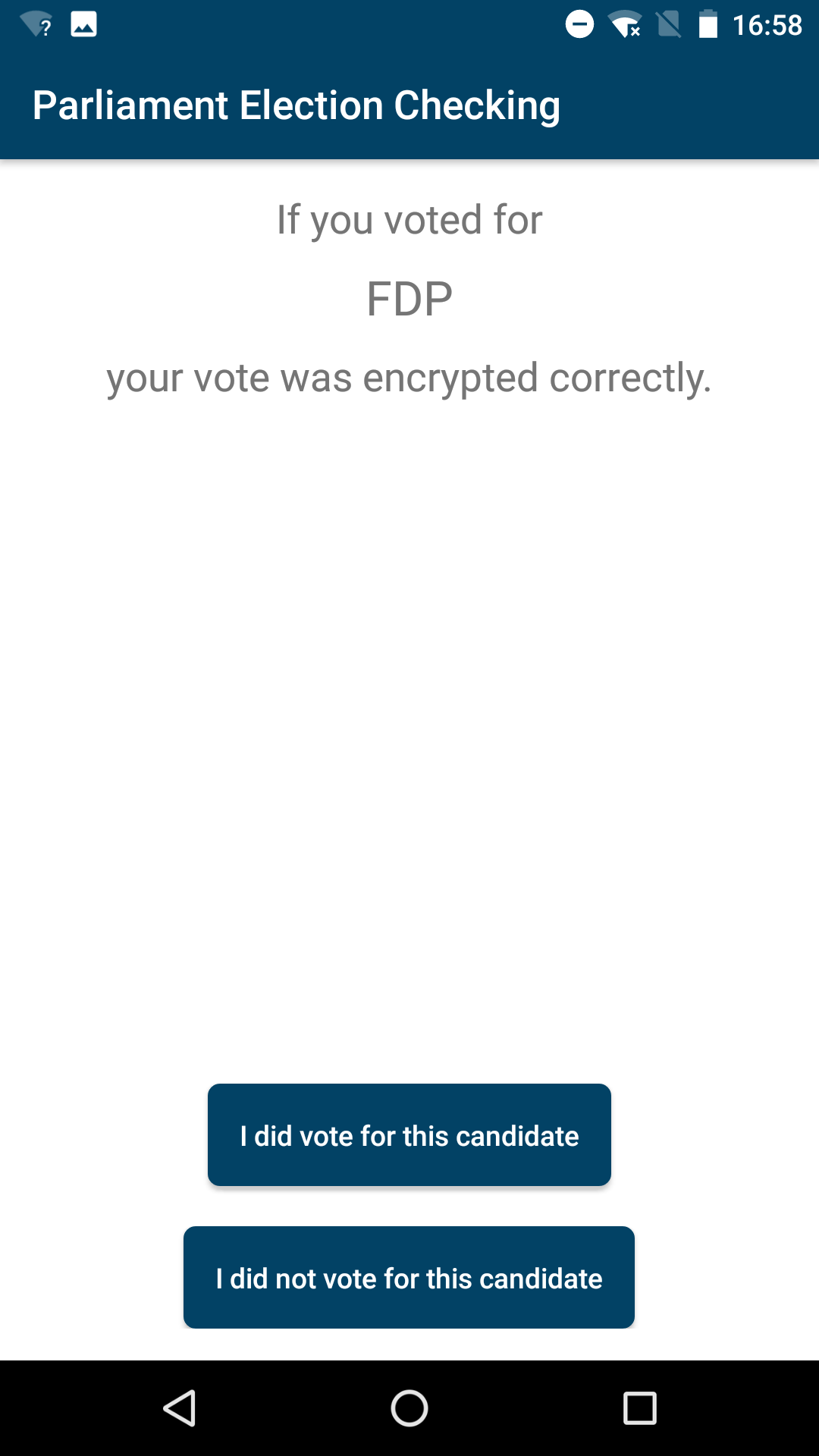

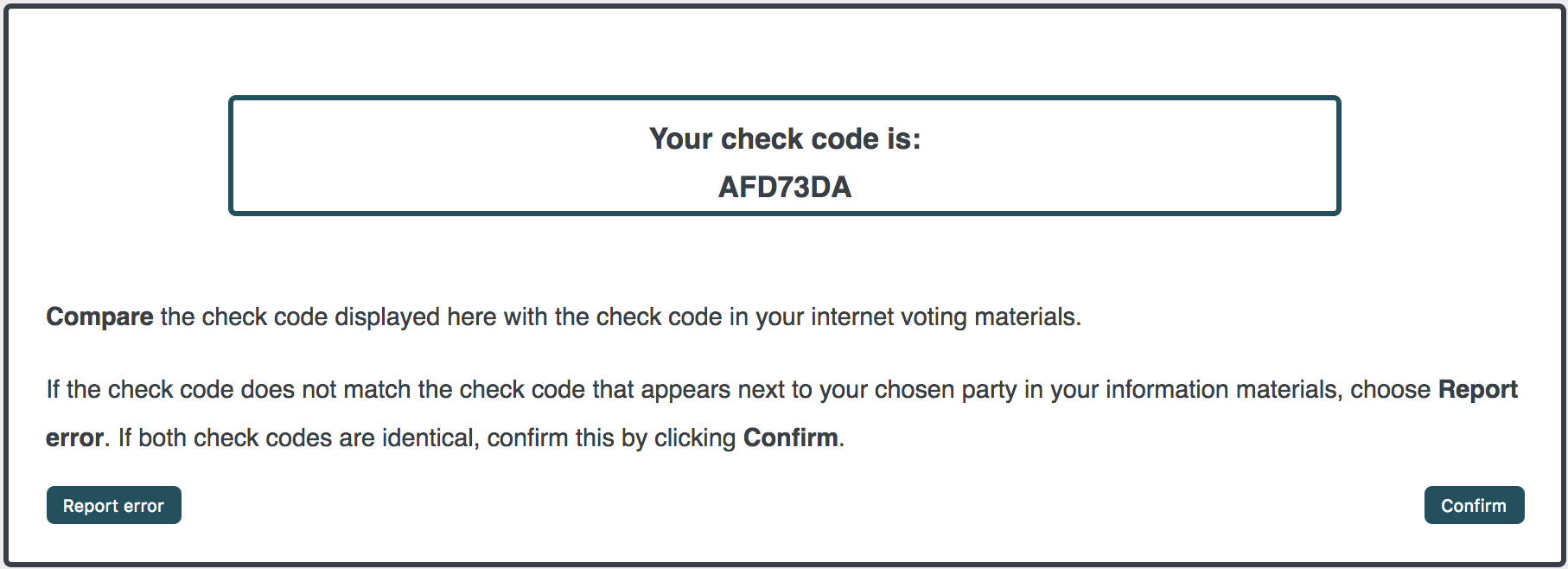

We conducted a user study testing the usability of two common verification approaches. One was a variant of a code-based approach (using paper code sheets), as described above. The second was the so-called challenge-or-cast verification [3,4]. Imagine having an assistant who prepares and casts a vote on your behalf. You would tell them which candidate to vote for, and they would complete the ballot, seal it and send it to the voting server. To verify your vote, you could then choose to challenge the assistant. In that case, you could ask them to open the envelope after sealing it, instead of sending it. If the assistant has cast a vote for a different candidate their manipulation would be detected. The actual implementation of this approach involves using a mobile app that scans the QR codes (representing the envelopes) output by the voting website i. e. a digital version of the sealed envelope. The verification step displays the chosen voting option so that the voter can ensure that their assistant has cast the vote as instructed.

We prepared two mock-up voting systems, one for each verification approach. The participants of our study were randomly assigned to one of two groups, each using a different system. They were told to cast and verify their vote for a specific party instead of expressing their actual political preferences. (We did this to protect the secrecy of their actual votes).

What they were not told, at the beginning of the study, however, is that we wanted to see how well they could verify their votes using the different verification systems. To test for this, we manipulated their cast votes. The manipulations changed the cast votes. This would be detected by their group’s verification. We then noted the number of participants, in each group, that detected the manipulations.

|   |

|---|---|

| Verification app | Code sheet and voting website output |

Vote manipulation with challenge-or-cast (left) and code-based verification approaches. In both cases the participants were instructed to vote for SPD.

Outcome of the study

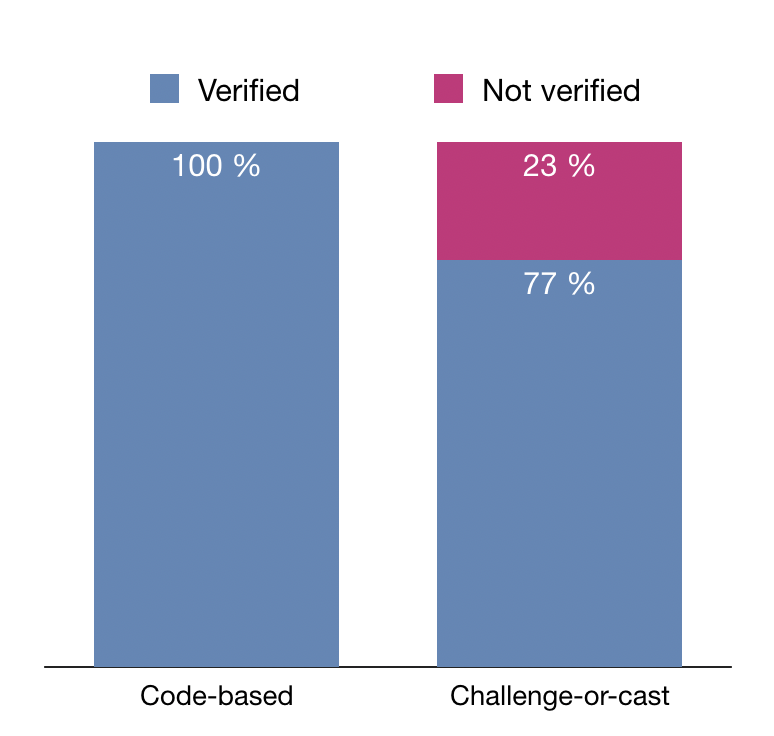

The results of the study revealed that the code-based approach was superior. All of the participants using the codes detected the manipulation, although some also complained about “cryptic-looking” codes. The challenge-or-cast approach performed poorly, with almost one-fourth of participants failing to verify their vote. Some expressed confusion regarding the complicated verification process, and the need to repeat vote casting from the beginning after verifying.

The study suggests that it is a good idea to use code-based verification during real-world elections. Indeed, the complexity of the challenge-or-cast verification has often been criticized in previous studies [5]. Yet, code-based systems can also be improved. Cast-as-intended verification is only one of the many factors assuring voting system security, albeit a very important one. If there are vulnerabilities on the server side of the system, the attacker has many more opportunities to manipulate the election results, without even having to compromise the voting devices. In fact, several such vulnerabilities have recently been revealed during an audit of the Swiss voting system using code-based verification [6,7]. As a result of the audit, it was decided not to use the system in upcoming elections [8]. A variety of measures should therefore be implemented to assure the security of the elections, from both technical and human perspectives

References

[1] Teague, V., Halderman, A. Security flaw in New South Wales puts thousands of online votes at risk

[2] Galindo, D., Guasch, S., & Puiggali, J. (2015, September). 2015 Neuchâtel’s Cast-as-Intended Verification Mechanism. In: International Conference on E-Voting and Identity (pp. 3-18). Springer, Cham.

[3] Adida, B. (2008, July). Helios: Web-based Open-Audit Voting. In: USENIX security symposium (Vol. 17, pp. 335-348).

[4] Neumann, S., Olembo, M. M., Renaud, K., & Volkamer, M. (2014, August). Helios verification: To alleviate, or to nominate: Is that the question, or shall we have both?. In: International Conference on Electronic Government and the Information Systems Perspective (pp. 246-260). Springer, Cham.

[5] Marky, K., Kulyk, O., Renaud, K., & Volkamer, M. (2018, April). What Did I Really Vote For?. In: Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (p. 176). ACM.

[6] Lewis, S. J., Pereira, O., Teague, V. Trapdoor commitments in the SwissPost e-voting shuffle proof

[7] Lewis, S. J., Pereira, O., Teague, V. How not to prove your election outcome: The use of non-adaptive zero knowledge proofs in the Scytl-SwissPost Internet voting system, and its implications for decryption proof soundness

[8] Swiss post press release. Swiss Post temporarily suspends its e-voting system